I recently saw this old Saturn advertisement which was obviously meant to promote their automobile brand. What the video actually does is demonstrate the unnecessary space cars take up. If you don’t have a moment to watch it, just imagine distant shots of people walking around in little groups of two-five people, moving in different directions on big empty roads. It’s an interesting way to show so much about the logic (or lack-there-of) behind aspects of modern infrastructure and transport.

After ten years of living in the regional town of Newcastle, Australia, I continue to be impressed at my options to get around in comparison to different places I’ve lived in the US. (Disclaimer to any disgruntled bus-riding Novocastrians reading, I know it could be better. Things can always get better.)

I compare the transportation options here to my experience growing up in South Carolina where you were lucky to get a sidewalk along most main roads. As I anticipate my upcoming trip to The South, I think about all the vast empty parking lots that define so much of the US. Outside of churches, strip malls, Wal-Marts and more, parking lots seem to stretch for miles.

Like many suburban children, I had a bicycle to go visit my friends on the streets around me, but that’s about as much ground as we covered. Bicycles were quickly forgotten as we got to middle school, and by high school, all kids were obsessed with cars, and I was no exception. Having a car was already an indicator of status, and more so, the make and model of car told the public what your family could afford to buy. Kids could get their drivers license as early as 15, and I could not wait! I had a job as soon as was legally possible and began paying off the golden slick four door 1995 Nissan Altima, with a cd player. It had a stick shift, annoying to learn, but worth it when it impressed boys.

I covered it with bumper stickers to display my personality to people “well behaved women rarely make history” etc. In a small town with not a lot going on, meeting friends for dinner, late night hangs in parking lots and weekend cruises to the mall was a new intoxicating freedom that I’d never known before. (I did total my car within probably a year of purchasing it, but we’ll save that fun story for another day.)

Looking back now I can see how owning a car instantly created a divide between rich and poor. Even as a child, kids who caught the school bus already were thought of as poorer than the car-pool kids, and by the time you got to high school that class divide had only deepened. The older kids get, the more aware they become of wealth, status and prestige. The popular kids had new sports cars. The redneck kids drove big ol’ trucks that they would take “mudding” on weekends. Some kids like me just had standard used cars, not cool but acceptable, and definitely better than nothing. If you didn’t have a car, you at least needed a cool friend who had a car to drive you around. The unspoken rules of youth culture influences for generations to come. I’ve been looking everywhere on Instagram for some young whipper snapper who is making it cool to take the bus. I can’t seem to find any, but they must be out there.

My high school’s infrastructure played into the theory that cars for everyone is essential. Have a look at the photo above to see how much space we built for high schoolers to park, and also how much space the actual school building took up. (It is two stories, to be fair.) Infrastructure like this indicates that individual car ownership is a normal, expected and welcome part of getting an education.

Driving to school every day took about 20 minutes of sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic. (I remember applying makeup and doing Spanish homework while driving because we went so slowly.) When the entire school district wasn’t crammed in, one-to-two person per car on the little road to school, the four mile drive took five minutes. The little two lane road of course eventually expanded to become four lanes. I now know that widening roads in attempt to decongest traffic actually tends to make traffic worse. This effect is called “induced demand” by economists. It means, in this example, every time you widen roads, more cars take up the extra space.

Google maps tells me that now the main road to my high school does come with sidewalks, and I wonder if they existed then, would it have crossed 15-year-old Alex’s mind to bike to school? Maybe if I had friends who did. A few times after school, a group of us walked to my friend’s house; he lived maybe two miles away. Those walks home were through uncharted pine straw piles and probably private property. We cut through woods and backyards like wild animals. A random Tuesday afternoon became a mildly dangerous adventure full of joy, fresh air and exercise.

It was not until I got to college that I saw people cycling all around me and began to think of the concept of riding a bicycle as a means to actually get somewhere. In the most mountainous place I’ve ever lived, I watched my peers pedal their perky buns up massive hills and then fearlessly fly down. I found myself a bike and began riding around campus and also off campus occasionally. The buses of Asheville graciously gave cyclists the option to place their bikes on the nose of the bus, great idea!

As an adult, I cycle minimally and cautiously. My eyesight is not great, and there’s nothing like riding a bike through busy traffic that makes you aware of your own mortality. But it varies from city to city. Once I became refamiliarized with cycling as an adult, I often bicycled to my summer job in Kentucky. Some colleagues thought it was cool, some thought I was nuts, and a few people made fun of me for wearing a helmet, as it’s legal not to do so. My favorite thing was the drivers of Kentucky who often treated me as though they’d never seen a cyclist before, swerving into the opposite lane to give me room. You’d think I was riding with an invisible tank around me.

At 22 I moved to Washington, D.C. and began regularly taking public transportation, catching the Metro. I took the red line train every day from my home in Takoma Park to the center of the city. I people-watched and talked to my neighbors who often took the same train. Big groups of us would ride out to clubs and parties together in the evening. I don’t remember feeling unsafe, although there were probably a few times I could have been more aware of my surroundings. I had my car in DC, but I tried to drive only when leaving town. This was 2009, before Google Maps. I had a Tom Tom navigator in my car, but in a city that never sleeps and constantly beeps, driving was just repetitively getting lost in front of aggressive, angry drivers.

After my time in DC I moved to Melbourne, Australia and was immediately impressed by their public transportation system. The tram route maps looked like a giant funky spider network, slinking out to the different suburbs. I flew in and rode into the city via the Skybus and then got around the city via trams and trains. The trams were fun but not without incident. One afternoon two aggressive tram inspectors caught me riding around without a ticket. I had been riding for free for quite some time because a Couchsurfing friend of mine had scolded me for paying.

“Don’t you ever pay to ride the tram! The tram is free. If they catch you just tell them you’re new to this country and didn’t know.”

It seemed sketchy, but I was living a strange new life on a waitressing budget. In my 23-year-old head it seemed mostly like a victimless crime. But as the tram inspectors loomed over me, not letting me out of my seat, I felt hard done by. I didn’t have any ID on me, but they took my flip phone and demanded I dial a housemate’s number so they could get my address. A fine for hundreds of dollars showed up in the mail, and that is when I began using a random abandoned child’s bike from the sharehouse to get around. Melbourne was good for cycling too, so it all worked out.

I could go on. The more I write the more the memories come. Everyone has a few public transport stories once they start thinking about it. I could write about the charming bus drivers of Port Stephens. I could write about taking ferries with jaw-dropping views in Sydney and watching Spanish Operas on super comfy buses in Mexico. It seems like every van’s a bus in Vanuatu and in London my French friend Marine saved me and an American friend from a night on the streets. She knew how to navigate the tube.

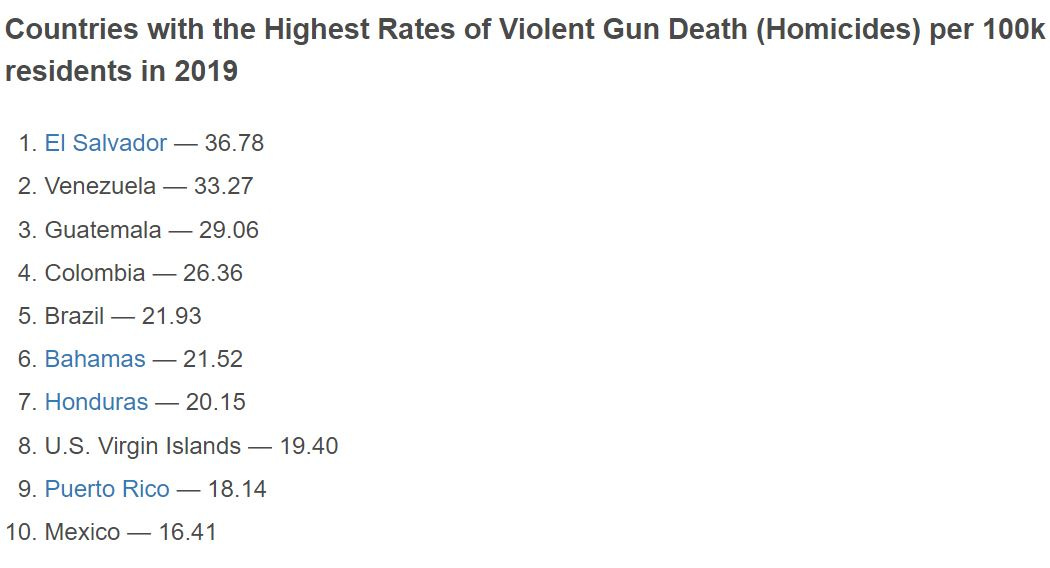

The left hasn’t gone nearly as hard it could when it comes to promoting public transportation, as The War On Cars discusses fantastically in this podcast. Could we reach across the political aisle with this issue? Could we all come together for a more wholesome, less consumer-driven, safer world? Guns are deadly and can be used for evil, sure, but do you know what kills more people than guns?

It’s not a competition, but I’ll leave you with some interesting stats.

Australia could do a lot better with footpaths. Even in Newcastle, there are major arterial roads with no adjoining footpaths. It does not encourage safe cycling or safe walking. Good on you, Alex, keep cycling, keep walking!!

I listened to this on my commute to work, like a podcast 😁. Interestingly. I have made a journey in the other direction, moving from bike or public transport everywhere. Not having a car or a drivers license until I moved to the US. I’ve tried to keep my my no-car life style. I ride my bike a lot more then most Americans, but as my less then 5 mile drive to work, taking up a huge amount of space in my Subaru all by myself, proves. I’m failing. I’m hoping that I can turn my kids into the cool whipper snappers who take the bus or the bike (although Oscar is already obsessed with cars, so I doubt it ) 😭