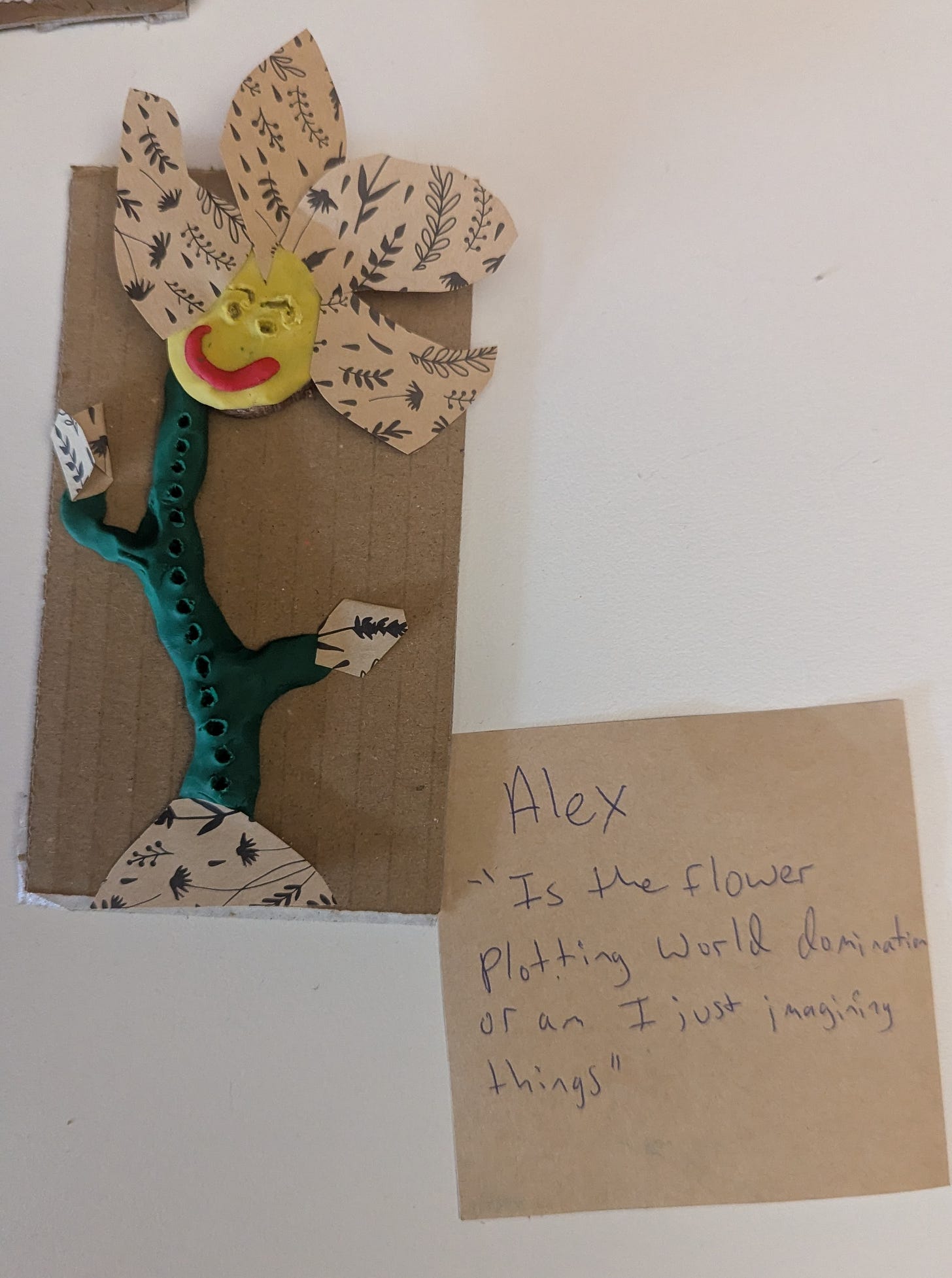

Last week during school holidays at the art gallery, my colleagues and I welcomed kids to drop-in sculpture workshops. We asked them to create art based on our beautiful new “Sticks and Stones” exhibition. The whole thing was adorable; they had strings, clay, beads, wire, sticks and more to work with, but my favorite part of this activity was the end when I asked the young artists what they wanted to title their sculptures. Of course because they’re like 6, the kids go with the simplest descriptor of their artwork. “Turtle,” “Mushroom Playground,” “Bob,” “Monster Truck” etc. I’m forever intrigued watching the free and intuitive way almost all children flock towards the art supplies, an idea, it seems, already forming in their head as soon as they see it. They know instantly that they want these tools in their hands to make something beautiful, but then when they have finished and you ask them honestly and earnestly what they want to title the work and why, they almost always pause.

The title is important, I told them. It’s the first thing the viewer of your art reads. It helps them understand what your art is about.

Let’s consider another field in which I’m arguably more familiar, journalism. A good journalist ideally conveys important and overarching information in the headline, so that readers know what type of article they are in for. Unfortunately instead you often see titles that are meant to grab your attention rather than inform you of the world. Titles could help us understand things better but it’s just as common to see them trick the reader. Titles manipulate, distract and most importantly make us smash that link!

The title is important. It is what makes the reader decide whether or not they will read.

I often write the title of my Substack right before I hit publish. I love that I’m given not only the header but the sub header to play with. I try to be direct with one line and more playful and silly with another. What would happen if I left all my Substacks untitled? Perhaps I’ll untitle this one as a bit of a social experiment. I was very excited to title my own work last week while sculpting with the kids.

Artworks with no “about,” and no explanation hit differently. The power in untitled leaves it up to the casual consumer to dictate what they are looking at. I’ve written poems about this and street art before.

“Titles” are similar to “labels,” although labels are broader. A title tends to be for an individual or a single work. A label can be a persona, a brand, a group, an identity.

In this New Republic article, titled The Art That Has No Name, the writer Ruth Bernard Yeazell writes:

”I suspect few pause to register how the label acquires its meaning from the convention it violates: Untitled signifies precisely because we have learned to expect that in the ordinary course of things, a painting will have a title. Every time our eyes search for one only to find its negation instead, we testify to the force of that convention.”

On the train home tonight friends and I talked about a different kind of label, the boxes we check when we answer questionnaires, for job applications, surveys or whatever. This conversation began with religion. At one point in time in Australia when you answered questions about yourself, you ticked a box to identify your religion. These days you’re rarely required to label your religion. The title of Mr. Mrs. Ms. etc. seems less and less as well.

I tend to avoid as many identifying factors as possible when I fill out a form. I answer honestly, but often I choose “prefer not to say.” Maybe children are doing something similar when they balk at conveying what they have just made.

Identifying yourself is surely different to identifying your art. But maybe I’m hesitant just like the kids are. I know what to do with the tools that I’m given, but I’d like it to be self-evident. One of my favorite things about kids is that many of them haven’t yet accepted the titles the world wants for them. They haven’t put themselves into boxes. Their free range minds are not even dreaming of defining themselves, their creations or anyone else.

As I write this Substack I realize I wish I hadn’t pushed the kids to title their work. They’re going to have to be summarising and summing up everything they do for the rest of their lives.

Titles and labels tell all in the news, in the art, in ourselves. They help us categorize and understand. In many ways, it’s probably great. Religious leaders and mental health experts agree, a sense of meaning and a sense of purpose is crucial to well being. But for tonight’s newsletter, I’m entertaining something different: A world without labels, without logic, without structure, without a need to understand. A place of pure art, feeling and being.

I am all for living in a world where flowers dominate!

On the kids labelling:- To have a creative label would need some time back and forth between the two parts of the brain. Sifting through the mountain of words available and coupling them with the creative process just completed takes some time and ruminating.